Chapter 7: Culture in the battle for Altadena

"In war: resolution, in defeat: defiance, in victory: magnanimity, in peace, goodwill." — Winston Churchill

Agenda

The night raid that lasted a week

Something neat I found on the internet

Dispatches from the soccer pitch

Shameless plug

Lessons learned

Epilogue

The gathering storm

On Jan 6, the National Weather Service put this on Facebook. Say what you will about the US Government and graphic design, this screams out, “this is so important, we decided not to take the time to make it look good.” If there’s a time and a place for superlative punctuation, this would be it. The next time you’re cringing at crimes against Art in a DOD PowerPoint briefing, just remind yourself that crappy design signals urgency.

The wind started ahead of schedule, early in the morning of Tuesday, Jan 7, 2025. Having been through this before, in our house facing the San Gabriel mountains, we had already barricaded the glass doors with furniture, secured the patio furniture, and, even set Colin’s pink shelf down, so it wouldn’t blow over (more later on the shelf).

I drove the kids to school, taking the city streets. It must have been while they were getting out of the car that a giant tree fell across Oak Grove Blvd, blocking the entrance to JPL and La Canada HS. I hurried home to get some work done while we still had electricity. During a lull in the wind, Abigail and I ventured out to survey the damage. It wasn’t too bad, really — Edison had aggressively trimmed trees away from power lines during the fall, and removed many of the eucalyptus “matchstick trees” entirely. At my neighbor’s house, the windows had all blown open. Richard invited us in (our dogs are besties) and I saw that it was hopeless — Venturi pressure had ripped the hardware off the windows. Dust covered everything. Richard swigged his coffee and, with characteristically good humor, quipped, “this place was due for a good cleaning anyhow.” Richard then wisely decamped to his daughter’s house in LA.

After lunch, Edison shut the power off, and then the kids came home at the normal time. I cooked dinner on a gas stove, and then we sat down for dinner. Oliver moved the candles around, playing with light and shadows for his photography class, as we discussed our family emergency plan.

Looking through the camera, Oliver asked, “Mom, what’s that red glow outside the window?”

As we heard the helicopters, we collectively regretted having unpacked our luggage yesterday. Martha said, “Eat up, kids, and let’s get ready to evacuate in case we need to. Pack clothes for 2 or 3 days. We should leave early so we don’t get trapped in traffic.” Martha’s aunt lived in Ft. Meyers, Florida. When her town was leveled by a hurricane, it became impossible to escape, even if you wanted to, so we knew we wanted to get a head start. I went outside to prepare the minivan, turned around, and saw a wall of flame higher than the trees, racing toward us at 60 miles per hour. The flame front was still a few miles away at this point, but it appeared to be much closer.

A wave of panic slapped me in the gut. “EVERYONE TO THE CAR NOW!” Our old apartment manager had told me about the 1993 fire, which had come all the way to Sinaloa Ave, at the end of our block. We had deliberately chosen to live west of that line, with the golf course affording a fire break, but this didn’t seem like the time to stay and find out.

The family switched into survival mode. As Uncle Ian says, “Fast is slow. Slow is smooth. Smooth is fast.” We deliberately collected clothes, the emergency binder with our important papers, the computers, the RAID server, school backpacks, dog supplies, and medicines. Our neighbors came outside to ask what the commotion was about. We directed their attention to the wall of flame racing toward them and shared our plans, and then they hustled back inside to pack. Martha departed first, with the kids and Abigail, in the van.

“Mom, where are we going?”

“Away.”

As the car inched down Hill Ave, Anjuli started texting from the back seat, and arranged for friends to take us in.

How many other people didn’t know? I loaded a few more things into my car, and then ran from house to house, pounding on the doors. Most were aware, packing and preparing to leave. One neighbor was standing in her driveway, taking pictures. She didn’t believe me at first when I told her that it was time to go. Still, some were totally unaware of the threat.

Me: Fire! Fire bad!

Them: Oh! Is that a fire? Do you think it will come all this way?

Me: Fire bad! Run!

From when we sat down to eat, to when I drove away, only about 30 minutes had elapsed, and the fire was notably closer than it had been when we started. The traffic through Pasadena crawled around branches and palm fronds. No police were to be found directing traffic. In the rear view mirror, driving through thickening smoke toward Glendale, the horizon glowed red.

Before joining Martha and the kids, I went to Walgreen’s for toothbrushes and toiletries, TJs next door to get food for breakfast, and then gassed both cars, in case we needed to leave again in a hurry. We landed with friends in Glendale, who, while lacking electricity, have big hearts and space to share.

The wind screamed all night, and the Watch Duty app told us that fire was creeping across Altadena, even igniting homes miles downwind, in Arcadia and San Marino. Could it be contained?

In the morning, the sun did not rise, and the power was still out, as a tower of wretched black smoke obscured the sky. I went to Ralph’s at 7am, meeting the other shoppers who were also stocking up in anticipation of another evacuation. Masks were long gone, and bottled water was going fast. Ralph’s would close just after I finished shopping, so the workers themselves could prepare to evacuate.

We had landed, completely by luck, not directly downwind of the vaporized remains of Altadena. But the threat was there, and transcriptions of the police scanner on Twitter showed the fire continuing to grow. Abagail and I met residents on every street, busy clearing branches in case they also needed to evacuate. But… where to?

Their finest hour

At 9:30 am on Wednesday, our neighborhood gardener & handyman, Wilder, reported that our houses were still standing. He had gone in early to check on his customers. Houses around the golf course were burning, but our block was safe for now. The ominous black cloud remained, and we considered our options from afar. It was unclear what to do. Stay put? Run? Where to? The internet and a hand-cranked AM radio told us that people all around Los Angeles were trying to find someplace to run to, but with visibility only 10 - 25 feet, nobody was going anywhere. Finally, the County asked everyone to simply stay put, but be ready to scoot. Abby and I went for a walk and dragged branches out of the street. Here’s the view of downtown LA.

After lunch, our friend Doug sent a picture, confirming that our house was still there. Apparently, we could return to our houses, so I took the kids to gather more clothes. Martha, who was really not enjoying the smoke odor, stayed behind. Driving up Hill Ave from the freeway, we dodged the trees and branches still littering the roads in Pasadena. Turning on Morada Pl, just south of the Altadena Golf Course, we found the air was only a little smoky, and there were no police or fire trucks to stop us. The house looked a little dusty and beat up, but otherwise solid on the outside. The garden hose was stretched out on the lawn, as it was on every home on the block. Inside smelled like a campfire, and ash had come through all the 90-year-old windows, leaving a gross layer on the furniture and windowsills.

The computer table was oddly out of place. The window above it was open, and footprints in the soot below indicated that someone had already been inside. Indeed, the nightstand drawers in the bedroom were open, along with the office drawers. We were perhaps fortunate that my daughter was in the midst of painting her room, so boxes were stacked everywhere, making it fairly difficult to access the other portable valuables. All we could tell that the thief took was the stack of $2 bills from the Tooth Fairy’s inventory, and a MacBook charger. The thief had not even attempted to enter our teenage boys’ bedroom, ostensibly for fear of tripping. I felt pretty good at this point at having taken my cryptographic keys and backup drives the day before, leaving nothing behind subject to ITAR.

The water was out, the power was out, and the house smelled like an ashtray. There was little incentive to linger, so we all gathered enough clothes to last a few more days, and walked down Morada Pl to do some reconnaissance. Maggie’s brother, Stan, was packing out all her and Dmitri’s musical instruments. One house on the north side of the street, at the edge of the golf course, had been vaporized. Two doors down, Cindy and Don (who are endowed more than the usual allotment of kindness, having adopted 4 children with special needs about 30 years ago) were collecting everyone’s phone numbers for an iMessage group. Their son, Kyle, was there, and he filled us in on what had happened in the preceding 12 hours.

When Kyle saw the smoke on Tuesday, he started driving toward Altadena from Upland. By around 4 am on Wednesday, the fire had reached our block. The wind had channeled a river of embers down the canyon, along the channeled wash along the edge of the golf course. Embers from lines of burning houses stretching north-northeast back to the canyon had ignited the brush and wood piles that the County’s concessionaire had stacked there (to the long-standing ire of the neighbors). These of course ignited, and so did the two nearest houses. Kyle, with a garden hose, climbed onto his parents’ roof and wet down the walls and roof facing the flames.

Glenn, Carlos, Dave (and his son, Dave Jr) all described having had an ominous premonition that compelled them to return home that morning. They arrived in time to join Kyle, using the remaining water pressure. Around 6am, flame poured across Morada Pl, around Flo’s Tesla (without damaging it at all), and into the 3 garages and 2 sheds on the south side of the street. Glenn said, “It was surreal. There was just a river of flame going down the driveway. Every time the wind shifted, I moved, just putting water onto the oak tree, because if that went up, the whole block would go.” Carlos and the Daves walked up and down the block for hours, wetting the roofs and extinguishing every flare-up. These heroes of the block contained the fire. If the trees or houses had ignited and thrown embers across New York Drive, the high-density apartments just to the south, in Pasadena, would have been next. Firefighters eventually arrived and offered to mop up the garages, but Glenn waved them off to concentrate on peoples’ homes that hadn’t yet burned.

Glenn later told me that he found a piece of brick that had burned a hole in the asphalt — on the south slope of his roof.

Over the next few days, we would piece together the events of Tuesday night and Wednesday morning. On nearly every block, somebody had stayed, or returned in the early morning, with a hose. Chuck and his sister-in-law stopped the flames from spreading further down Sinaloa. Van on Mar Vista told us how three people on her corner had spent the night with buckets extinguishing spot fires. The other two departed in the morning, leaving Van, who had a generator hard-wired into the gas line, in charge of their houses. Linda and Augie, whose dog is another one of Abigail’s besties, had taken off when they smelled the smoke. With a eucalyptus tree in their uphill neighbor’s yard, their newly remodeled house didn’t stand a chance. Still, as the flames approached, their neighbor, a veteran and LAPD officer, went in and rescued some precious keepsakes, including Linda’s mom’s cookbook. He tried to save the house, hosing down the embers as they fell on the roof, even as one waves of looters ran inside. The house burned, but the fire didn’t spread further south. Another Dave, a retired firefighter on Meadowbrook, a few blocks away, would use shovelfuls of soil to quench fires on the fences and yards all along his block. Aaron, on Altadena Drive, evacuated his family, then turned around to come back. Tracking the progress of the fire as he approached, he made some phone calls, warning that the “90210 house” at Altadena Dr. and Porter, was threatened. Sure enough, it squawked across the scanner, and the firefighters raced to save the historic Craftsman that was home to Luke Perry’s character on Beverly Hills 90210. Aaron hoped that would also protect his house, next door, but to no avail. He was there, with a hose in his hand, his truck facing downhill, as it burned to the ground.

Later, a Sheriff’s deputy would give Aaron flack about defying the evacuation order. Aaron asked, “Did you see me there on the night of the fire? With my truck facing out of my driveway and the headlights on?” The deputy replied, “Yeah, I saw you.” Aaron asked, “Well, why didn’t you stop and help me?” The deputy said, “Do I look like I’m prepared to fight a fire?”, to which Aaron replied, “DO I look like I’m prepared to fight a fire?” This represents the crisis of conscience that overtook everyone whose lives were touched by the fire — first responders and residents alike. Did I do enough? To save what I could? To stop the fire from spreading? To protect other people from experiencing the same loss?

The kids’ school, Flintridge Prep, has every 8th grader do a community service project. Colin’s was to make a free food pantry, and just before Christmas, he had negotiated permission to set up a shelf at the recycling center in West Altadena, walked the neighborhood to collect donations, and stocked it with free food. Just after New Year’s, we found a pink shelf a few blocks away with our local Buy Nothing group, so he and his buddy Ryan brought it home, in preparation for upgrading the food pantry. So, he set it up in the driveway, and filled it with more donations. I also figured that foot traffic would discourage additional looters.

The kids and I hopped back in the car with our supplies and drove up Sinaloa to check on our friends’ houses. The street was mostly empty, and we passed one ruin after another. Utility poles loomed over the road at a 45º angle, their bases burned through, held up by the tension of the wires themselves. We saw that most of Braeburn, along with our friends who had just moved there, had burned. Continuing up to Altadena Drive, we were surprised to see friends at their house, one of the few still standing up there. We stopped to help them pack up their artwork and silverware. As we drove away, a perfectly well-preserved ranch home, two lots away from our friends, erupted into flame. I called 911 to report it, and the dispatcher replied, “ok, I’ll let them know,” with a tone utterly lacking in confidence. Spying a green fire truck, from the Angeles National Forest, I drove over the few hundred feet alerted the forest rangers. They drove over, sprayed their remaining water on our friends’ house, and then sat with our friends and watched their neighbor’s house burn to the ground.

We returned to Glendale, walked the dog, cooked and ate dinner in the dark, and made a list of everything to do tomorrow — file insurance claim, clean, yadda yadda.

Thursday morning (Jan 9), I was the first one back, at 7am, except for the lone Sheriff’s deputy parked sideways across Hill Ave. An attorney who arrived shortly after me protested until he was shaking with furor, to no avail. I set off down the street to see what I could see. The power lines looked ok. Linda & Augie’s house had a giant orange flame coming out of it, which I reported to the deputies guarding the next street over. It was the gas meter, flaring off. I met an elderly neighbor on New York, walking his dog, and brought him two gallons of bottled water from my car. A crowd was forming at Hill, and still, nobody was getting through. The neighbor on the corner, Kip, returned. We hugged, cried, shared a banana, and then walked in through his front door on New York, and out his back door into the neighborhood.

I started by checking in with the neighbors. Diana was walking her dog. She had just seen an unfamiliar man with a backpack leave a house on our block. They called 911 and reported it. Diana, Carlos, and their boys had stayed the night and had started cleaning, drawing power from an inverter hooked up to their truck. After inspecting all the houses and yards on my end of the block, I set up our emergency generator out and fired it up, plugging in our neighbor’s refrigerator, my refrigerator, and my chest freezer full of salmon, while I started clearing branches from the yard.

After a time, the Sheriffs received orders to admit residents, on foot only, and more people appeared. Suddenly, a house on Mendocino, across the golf course from us, erupted into flame. This was a wake-up call. It wasn’t over yet. The weather forecast warned of more wind, and Carlos said that he had already extinguished a few flare-ups that morning. We filled up buckets of water from Carlos’s swimming pool, carried them up ladders, and tossed them onto roofs.

There were branches and leaves everywhere — and also charcoal cinders that told us we had been lucky. My back-yard neighbor from New York Drive appeared — he had conveniently installed a new gate in our shared wall, along with pool with 80,000 gallons of water. We started a new text message group for the neighbors on NY, and alerted them to the need to remove fuel.

You can see that the pine needles that had piled up on the golf course fence had trapped the embers, and burned in place, leaving a scorched line, but the adjacent aloe was unaffected. Similarly, the hedge in front of Glenn’s house trapped embers and made a line of flame — but that was 20’ from the main house, apparently, enough to be defensible. The rock wall that Dmitri had built out of his old driveway had similarly stopped the flow of embers, saving Stan Edmonson’s sculpture garden — and Maggie’s & Dmitri’s house. The ivy on the hedge seemed perfectly fine, and the oak tree trunk was far enough from the wall to survive the heat. It seemed that the way to reduce risk was to clear brush from around houses.

While most of our house is stucco, there are wooden gates. There wasn’t enough time to clear all the leaves, or remove all the fuel that had collected along the golf course fence, so I moved some low walls from our ninja obstacle course in front of of them, hoping that would keep any new flows of debris or embers away from the main structure, shut off the generator, and returned to Glendale for dinner. This seemed like a sustainable pattern: sleep and eat in safety, return daily to clean and suppress flares, and gradually recover.

We were just starting to understand the nature of the disaster. Joe Morrison sent me a satellite radar image that Umbra had captured. It showed pockets of surviving structures east of Lake Ave, around the golf course (not in the frame), and where the firefighters had held a line at Lincoln Ave. In between was bleak.

This disaster recovery was brought to you by iMessage. As the text groups grew, we came to realize that every block had 4 or 5 people remaining, who were dousing flames, removing fuel, and turning off water valves. A few people, like me, connected groups to each other. Only one fire truck had driven by our street. Carlos said he talked to them, and they said it was the worst they had ever seen. Carlos said, “It must be bad in Palisades, too.” The firefighter replied, “I just came from there. This is worse. Much worse.”

Commercial interruption: Carlos is the world’s best art framer. His license plates say FRAMNATR and FRAMEMAN.

The grand alliance

That evening, the neighborhood text groups erupted: the sheriffs had been ordered to seal off the area. Everyone inside was ordered to evacuate, because “this is an evacuation area.” The County stated that because there are gas leaks, nobody should return to their homes, because of risk of explosion. Meanwhile, we heard that looters were already there, with metal detectors and night vision goggles. For those who had lost their homes, it seemed like a race against time to sift through the ashes, and for those who still had houses, a race to protect it. Fire and police trucks drove by every few hours, covering their routes much too fast to notice anything. We heard of a house that burned on Thursday evening, and firefighters who stood and watched.

The remaining people on our street started to take an inventory of buckets and fire extinguishers. Discussions were in play about how to pool resources and prepare. “Screw this,” I thought, and I wrote, “Let’s do this properly. I’ll go to Home Depot and buy a whole bunch of supplies. I’ll text you when I’m on my way.” So much for soccer practice, or the Caltech entrepreneurs’ dinner that had originally been planned for that evening.

After dinner, I gathered up supplies and drove to Home Depot, where the workers were stacking piles of fire extinguishers, work gloves, safety goggles, … pretty much everything we needed. I grabbed a stack of buckets, a case of fire extinguishers, plus gloves, and solar lights (no streetlights). They were out of masks. Three employees checked the computer inventory and confirmed, without a doubt, they were out of masks.

In the parking lot, I walked by a truck full of shovels and buckets. “Hey, it looks like we have the same idea.” The driver turned out to be Aaron Lubeley, a take-charge, non-nonsense attorney, who was talking with Tim, manager of the Pasadena Home Depot. Shortly after the fire started, Tim had started transferring inventory from every Home Depot store around. He was asking Aaron how to help. Aaron’s plan was that even though his house was gone, we could still prevent the disaster from getting worse, by supplying and sustaining the residents who were staying behind. When he learned that the store was out of masks, Tim said, “wait here” and disappeared into the stockroom while Aaron and I discussed strategy:

Sustainment. People on the inside need to be resupplied, with food, water, gas, buckets, PPE. Aaron had already set up a relief station in his driveway. A steady stream of people were coming by to get food, fuel, and tools. We needed the ability to bring supplies in.

Information. The residents had self-organized, block by block, but there was no political entity to coordinate. Town Councilmember Connor Cipolla, who was still in his house, near Aaron, was getting no information from the council. (California’s Brown Act prohibits elected officials from doing business outside of official meetings, so a Slack group is right out.) The local fire commander had given Aaron his mobile number, so we had a path to call them directly. That was apparently how things were going to get done.

Narrative. People on the outside had no idea that residents were still fighting to contain the fire, that looters roamed with impunity, or that there were no firefighters. Governor Newsom and Supervisor Barger announced rules that made no sense to us on the ground, and they changed every few hours. Not only did they not have a plan, they apparently also had no way of communicating strategy, doctrine, or a vision to the police and firefighters on the ground. It was a complete failure of the political system. Aaron and I would reach out to our political contacts to provide firsthand intel. We would also need to give the media a new story — rather than obstructionists putting firefighters’ lives at risk, we needed to be thought of as community activists, making a difference.

Access. We needed ways to get residents in and out.

Tim returned with a box full of painters’ masks — the good ones, with activated charcoal, and we headed back to Altadena at about 9 o’clock, via different routes.

I called Carlos and Don on the way. They had interrogated the officers at Hill, Sinaloa, and Allen, and determined that the ones at Sinaloa were most likely to help. They met me there together and the deputies let me carry supplies up to the police line. After the third trip, it the deputy in charge got restless. I had the feeling he was antsy that he wasn’t part of the solution, and he wanted to help. He had been talking with residents all day, and knew full well the precariousness of our situation, but there was no information going either up or down his chain of command. On my trip from the car, carrying my tote bag of supplies, he lifted up the police line and whispered, “Godspeed.”

Carlos’s boys and Dave joined us at the access road to the golf course, and we started filling buckets from the swimming pool next to the burned house. With our hand trucks, we set 8 of them near the golf course road, one near Glenn’s garage, and spread out some along the block, to be ready for anyone to grab at a moment’s notice, and then set the rest in front of Carlos’s house.

The young men took the first patrol shift, at 11pm, and then Carlos and I took over at midnight. In the dark, it’s easier to see flames. In the golf course itself, trees were still burning, and flares would occasionally erupt spontaneously out of the ground. It was dark and smoky, and I’m old and nearsighted, so it was difficult to tell from a distance exactly what was on fire. We started on the western perimeter, with a bucket and a shovel, around the perimeter of the golf course, and quickly met a detective from the Major Crimes unit. He explained that a) he knew we weren’t looters, because he heard us coming a mile a way, and b) detectives were all over, lurking in cars. We briefed him on our plan to look for signs of fire, and he wished us luck as the radio called him to assist in apprehending a burglar a few blocks to the east.

The chemical safety goggles that I’d gotten at Home Depot made a big difference, preventing our eyes from stinging, but walking uphill was still an ordeal, and our lungs were plainly struggling. Still, we walked up to Meadowbrook and assured ourselves that all the flames we saw were from gas lines, not from wood. Returning to the golf course, I saw a glowing ember on the ground, across the access road from the burned house. The heat from the house fire must have ignited the roots.

Indeed, it was a root fire. We learned about this in wilderness survival class. It’s bad. You have to get on that, or any day, the whole forest can erupt again. In fact, that’s what they think started the Palisades fire. The ground was hot to the touch, and, digging down, we saw glowing red and hot, white ash. We called Don over to help. Don filled buckets from the pool, Carlos carried them over, and hoisted them over the chain link fence, and I fed the water into the root system. This is one in a line several large pine trees, where ignition could spread to Pasadena.

After dumping about 50 buckets full onto this tree, we continued up into the golf course. There was a pile of logs, from a 2’ thick tree trunk, that were still burning. And there was a hole where a stump used to be, pouring smoke. We decided to prioritize the ones closest to structures and to other trees, and while Don and Carlos dealt with another root fire, I continued uphill on foot to scout for other risks. There were more root fires. There were logs, just burning. I saw a LA Co fire truck in the golf course parking lot, the first fire truck we had seen. I passed burning poles to approach the truck, introduced myself, and explained the situation. After much cajoling, they reluctantly agreed to go take a look at the large stump fire. They drove away, and Carlos told me that they looked at it, and decided to leave it alone. “I could put 500 gallons onto it, and it wouldn’t make a difference.”

As I walked back, on the street this time, the lights on a pickup truck turned on. It was another detective, and he gave me a ride to base camp. I asked him if he thought it was a good idea, what we were doing — suppressing fires, and maintaining a presence to deter looters. He said, “That’s what I’d do. Good luck.”

I left Altadena and returned to Glendale at about 5 in the morning. The power was back on, so Friday morning, I caught up on work, and sent some emails describing the situation. The information in the news was still, shall we say, unsophisticated? They were warning of more high winds, Saturday night. We had time to prepare.

On iMessage, we compiled reports on the sentries — the National Guard had arrived — to facilitate sneaking in through back yards of houses facing New York Drive, without overusing any one entrance, or making the routes obvious to looters. Some paths had latches, while others involved screwdrivers. We helped neighbors reach their houses to do what they needed to do.

Friday afternoon, I drove back to Altadena, slinked through Gene’s gates, and reached home. Once you’re inside, the cops don’t bother you, and if the residents see someone they don’t recognize, they stop and interrogate them. Physical security felt pretty good. I opened the windows and doors to air out the smoke, turned on the generator for a few hours, and, now that the water was back, gave everything a good hose-down. The buckets had been moved and refilled since the previous night. Some neighbors stopped by to thank me — said they’d used them to put out some fires, and then refilled them to be ready for the next one. The self-serve system was working. Some of the food had even been taken!

There were a few cinders on the driveway that hadn’t been there the night before. The wind must have brought them in the night. I checked all the neighboring houses, feeling for heat and sniffing for fresh smoke, then threw some more water onto everyone’s roofs. There was a 30’ wide circle of ash on the golf course, a root fire that radiated warmth, but there was nothing we could do about it.

For stopping the fire, and then staying to keep at it, Carlos was a star on the television news. News teams from Australia and the UK came by to interview him, not to mention the local stations. One of the reporters turned out to be a preschool friend — Natasha remembered coming to a toddler birthday party at our house! Having explored the area and interviewed firefighters and residents, she agreed that a mandatory evacuation made no sense under the circumstances. In interviews, Carlos emphasized how neighbors were working to protect their homes, and also the rest of Los Angeles, from another firestorm. Carlos didn’t want to be the hero, of course. I said, “Remember the movie, Hunger Games? You’re the girl with the arrows.”

Aaron was back (commuting in, getting his truck through with a police escort), trying to get permission for select community members to get authorization to come and go. Or at least, get a truckload of supplies in. There were no more 5 gallon gas cans to be had, anywhere. He was also meeting with reporters to explain the important message that residents were still here to prevent loss, that the firefighters were massively overwhelmed, and that the authorities were actively hindering the efforts of Altadena residents to prevent the fire from reigniting and spreading.

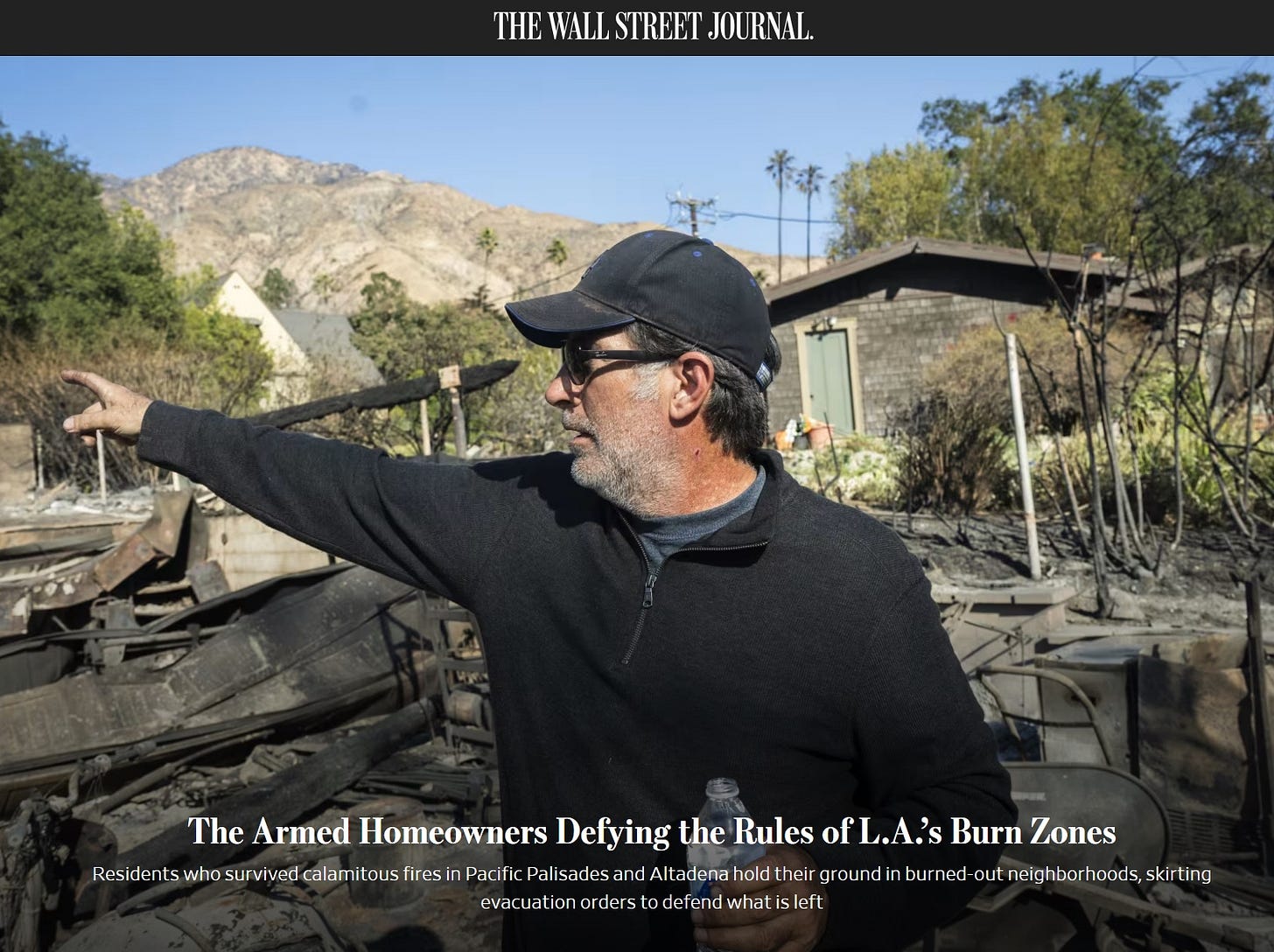

This was a wakeup call that news outlets have their own narratives to sell, and that part of our challenge was to align their purpose with ours. How would we convince reporters and their editors to tell the story the way we saw it? Aaron was absolutely furious with the editor of the Journal, by the way, for portraying him as an unhinged vigilante, which he is absolutely not. Aaron is one of the most clear-minded, calculating, righteous people I have ever met. He’s the managing partner of a law firm, and you do not want to be on the other side of the table from him. He spearheaded the media relations strategy, and coordinated relief efforts deep within the burn zone.

The hinge of fate

Friday night, a curfew went into effect at 6pm. It was smoky when I left at 8 pm, out the back way. I returned to Glendale in time to walk Abigail, . Saturday (Jan 11) morning, the National Guard had taken over the sentry duty, and the gas was finally shut off. That at least removed the “gas explosion” excuse to press people to evacuate. But the sheriffs had moved the roadblock south, to Topeka St. in Pasadena. The reconnaissance teams probed entrances over the course of the morning. Some gates that had provided access had been shut. The guards, who didn’t know their way around (one said, “go to 26 San Vincente to show ID and enter” — which is an address in Palisades, 20 miles away) told one of us that the whole town was being treated as a crime scene, so everyone should stay away until they have had a chance to search for survivors and bodies. Gavin Newsom stated that he was looking for someone to punish for this. Enough was enough; it was time for me to go back and take charge. By the afternoon, the team had found a way to reach New York Drive through side streets, and I arrived a few hours before the curfew. Open the doors and window, turn on the generator, and get to work.

Up until now, I hadn’t ventured more than a few hundred feet before something cropped up. I wanted to connect with the rest of the Resistance. I called Chuck to ask for a ride, and we went to the very top of the hill, where my friend, Stephanie, asked me to check on her house. Her neighbor, with a hose, had reportedly saved his house and hers, the only two remaining structures on their private road at the top of Loma Alta. The drive to the top was surreal, passing one pile of ashes after another. A few utility and fire crews were working at the top of the hill, inspecting one lot after another. When we reached Stephanie’s, I was floored to find everything still there, almost pristine!

Behind the camera was a steep hillside, charred to the roots. You can see what the cinder block wall did — Stephanie’s car is completely fine, and so are the parts of the structure shielded from heat by the wall that wraps the property. There’s even a motorcycle leaning against the other side of that wall, not even slightly singed. The iron gate allowed heat through to scorch the siding, and that’s where the hose came into play.

On the way down the hill, Chuck dropped me off at Aaron’s, where he introduced me to the Fox News crew, Derek and Judd. We agreed violently about the need to get the message out that the self-organizing residents of Altadena was the force preventing an even greater disaster. What could a reporter do? We needed a hero, and Derek was going to make Carlos into a hero. Derek had the power to plant ideas into government officials, by how he asked questions. How do you let only a few people back in? There’s no legal or bureaucratic way to do that. What about a “soft opening?” Later in the week, Rep. Judy Chu would announce a “soft opening” for Altadena, for one or two members of a household to get what they need, and not stick around for too long.

Aaron and the others up there had been spending the day directing firefighters to hotspots, repairing generators, and exchanging information. Root fires abounded here, too, sometimes creeping under driveways and out the other side. Los Angeles firefighters have many abilities, but fighting subterranean fires are flat out not their thing. Their biggest difficulty was fuel for generators — it was difficult to get it into Altadena and up the hill. I took a couple shovels, a pocketful of granola bars, and couple of Chick-fil-A, and walked back down to Morada.

Walking down the hill, I passed workers laying out new utility poles, shutting off gas valves, and coiling downed power lines. It made sense not to let everyone back in — some roads were blocked entirely by utility trucks, and having a lot of civilians around would definitely slow the work down. The fire extinguishers that we had originally stacked on the curb by Carlos’s had diffused throughout the neighborhood. If you needed one, you’d be able to look around and find it.

Reaching Morada, I saw someone cleaning a grill. It turned out he was a caregiver for the disabled veteran who lived there. I had to go in and say hello! Fernando, who sacrificed a leg to the GWOT, had refused to evacuate, and had been composing happy dance music on his phone all along. He also was complaining about some pain in his foot. I left him with a bag of chicken sandwiches and a promise to send help.

We held a neighborhood meeting at Carlos’s. Don was checking out — he was beyond his limit. Remaining on Morada were Diana and Carlos, their son Noah, Dave, Andre, and me. (Flo and Glenn had previously booked a vacation in Cancun, so they had rotated out a few days ago.) Were we the Resistance, or the crew of the S.S. Minnow? Fire risk seemed imminent, there were piles and piles of leaves, the authorities were not listening to us, and even if there were firefighters, we had low expectations for what they’d be able to do. I wanted to go “home” to Glendale and stay with my family, but, in the immortal words of Jerry Garcia, “someone has to do something, and it’s just incredibly pathetic that it has to be us.”

Neighbors had spent the day trying and failing to get in. Who was staffing the checkpoints, and what orders they had, changed throughout the day. Somebody high up wanted us gone, but fortunately they weren’t willing to come here and learn about the conditions on the ground. Even though they were compartmentalized, and we had an intelligence network, they were making progress at filling the physical holes. If I were to leave now, who knows when I could return, and then where would the block be? So I stayed. And Andre, who is a doctor, trotted off to check on Fernando.

What news from the outside? What was happening? We heard a crackdown was coming, and the sentry duty would be assigned to young hotshots who would follow simple directions: don’t let anything or anyone in.

By Saturday night, we had thought most of the fires were out. We had spent so much time on our local area, though, even though we knew that there were other residents nearby, there were only a few on each block. I would later run into one at the shoe store, from the east end of Meadowbrook, whose story was similar to ours — check yard, throw water onto a hotspot, refill bucket, repeat.

Saturday night, I was visited by a friend in the Sheriff’s department. He had specifically requested the assignment, and the graveyard shift, because he wanted to help. We chatted for a bit, and as I was filling him in on the history, new flames appeared on Mendocino. He called it in and drove away to take care of it. The wind picked up again at about 1am, not nearly as strong as before, and by 3am, the hilltops started to glow again. I set an alarm for 2 hours and went back to sleep.

After a fitful night, I carried my camping stove and cookware over to Carlos’s. Diana brought coffee, and Don brought breakfast from Burrito Express to the checkpoint. Carlos said, “My shoulder is really sore today.” I replied, “that was probably from lifting 150 gallons of water over the fence on Thursday.” Cheryl arrived, in the back of a cop car. It was definitely the S.S. Minnow.

Fire trucks arrived, at last! From Idaho! We briefed them on the history, pointed out the historical burn scars, and then the 40’ wide ash circle above an enormous root fire on the golf course. They said, “lemme call our commander over to check it out.” They drove a few minutes later, and I briefed Tim and Tom on what we had been doing since Tuesday. They went off exploring, while I went to break into Jennifer’s house to water her house plants. On the way there, I stopped a deputy from the Compton station, and explained what I was up to. “Sounds good! Stay safe!”

After removing the hinges from her gate with my handy Kershaw multi-tool, and taking care of Jennifer’s plants, I checked the back yard and discovered the tree that grows, objectively, the most delicious oranges in the world. I filled a bucket with those and handed them out to firefighters and utility workers on the way back. Our street had become the de-facto staging area for all the work crews, which made us feel a lot better about physical security.

Tim and Tom from Idaho returned, and we got to talking about root fires again. “We're from Idaho. We're wildland firefighters,” they affirmed. The tree that we had doused on Thursday night had been saved, but many more were still burning underground, both in the golf course and on properties. It would be a matter of revisiting them every day to make sure they stayed out. I forced some oranges on them, and they gave me their phone number and asked me to text them if I found any more hotspots. In parting, Tim said, “Oh, and that root fire? We’re going to drop 10,000 gallons of water on it and turn it into a giant puddle of mud.”

The HUMINT team reported that nobody, and nothing was getting in. Both National Guard and Sheriffs were at each intersection, to keep an eye on each other, and patrolling the main roads. Nobody was able to just waltz in anymore, and the checkpoints were also ordered not to allow supplies in — not even food or water. The idea was to starve us out. We would have to figure something out between now and lunchtime, so someone went to chat up all the guards and identify the most promising locations.

Meanwhile, I took off to explore the rest of the area, which I’d never really had time to, before. At the top of Hill Ave, I discovered that the entire hillside was warm and smoking, so I called that in, and the Idaho folks came by later with a water truck. At the western end of the street, at Mar Vista, there was the unmistakable sound of a generator, so I knocked on the door as a police car drove by, patrolling, behind me. Van and her two dogs were the lone holdouts of that intersection, after the two residents on the corner opposite had, similarly, suppressed the fire on Wednesday morning. Van took me on a tour to inspect the properties and look for any risks. “Was that gate always open?” “It was closed two hours ago.” Sure enough, we found a house that had been recently looted, a block from where the Sheriffs and National Guard were stationed. So much for physical security.

We called 911, and were told that they could only respond if only the homeowner reported it. Van took it in stride and called the woman who owned it, and then a few minutes later, 4 patrol calls screeched in. “Had we gone inside?” they asked? “Of course. How else would we know it had been burgled?” They asked us to leave, and to avoid checking it out ourselves in the future, so I walked away. A block away, a Sheriff racing to the scene stopped me to ask me what I was doing (wearing my best Hawaiian shirt and Panama hat). “Um, I’m the guy who called it in. The reason you’re here now. Here’s my ID.” A few hundred feet later, I called 911 to report another door that was hanging open, and the dispatcher laughed at me.

This whole time, I was smelling the air for smoke, feeling the ground for heat, and listening for my phone to bing. There was so much communication going on between the different resident groups, that I would have to fully charge my iPhone 3 times a day. (Plug for having a jumpstarter battery back with a USB port).

If I was going to spend another night here, we’d need to upgrade the sleeping situation, so I visited some friends’ houses, checked their back yards, sent them pictures to reassure everyone, and borrowed an air filter. With the house open during the day, and the generator and air filters running at night, it wasn’t so bad, really. As the sun set at 5:30, the foul odor returned, and we all retreated indoors.

My sheriff friend returned that night, with a can of gasoline and a bag full of supplies — protein bars, tissues, energy drinks, toothbrushes — for Colin’s pink shelf. Firefighters and utility workers would continue to stop by to pick up something over the succeeding days.

Closing the ring

Monday morning, the Resistance gathered again at Carlos’s for coffee. Andre had to go back to work to see patients. This was the first day we didn’t have to start the morning by dousing a fire, so we decided that the best use of our time was to clear out the leaves and branches. Aaron reported that, higher up the hill, the National Forest firefighters had taken over the battle with root fires, so their biggest need was gasoline for generators.

Not long after that, another deputy drove up with 5 gallons of gas. I put the call out on Twitter, and Grant said he’d be by later with some. Our preschool friend, Caitlin, called with an offer of hot lunches, cooked by World Central Kitchen at St. Francis School. I looked around, counted everyone I could see, and asked for lunch for 40.

Caitlin came to the checkpoint at Allen, where the senior officer had been briefed that we were bringing in lunch for the firefighters. They were under strict orders not to allow residents to receive supplies. Caitlin is no fool, and her kids carried the boxes of food to load into Carlos’s truck. All the same, they were clear that if I crossed the yellow line, they would not let me back in.

Every firefighters would tell us that they were glad that us residents were here. It would be better if there were more of us, because there was a lot of territory to cover. I made sure to visit each of the guard stations, with my bucket of oranges.

At one of them, I was told “Oh, the guardsmen aren’t allowed to accept gifts. They are supposed to eat the rations they were provided with.” As this contradicts everything I have ever learned about the Army in my over 30 years of defense contracting, I said, “Oh, well then, I’ll just leave these oranges here on the hood of your Humvee and leave you to your duties.”

My friend, Grant, brought 4 5-gallon jugs of gasoline, and set them down outside the yellow line. The guardsman pretended to look the other way as I dragged them up Sinaloa Ave. Aaron was preoccupied, so Van offered to pick them up and take them up to the Altadena Drive relief station.

The determination of the guards to fight the residents was wearing down. Somehow, Stan reappeared, and went to work raking leaves all along the block. Some LA County firefighters drove by and told me they were looking for debris that would become fuel in a future fire. “Well, have you come to the right place!” But they were not allowed to enter property — they could only take it from the street or adjacent. So all we had to do was … haul it a few feet closer, and then they could clear it? I recruited some more neighbors from adjacent blocks to help, as the leaves that had been green and fireproof, a week ago, were now ready to burn at the earliest opportunity. We found cinders the size of golf balls among them, along with singed paper and building materials, so apparently we had gotten lucky, before. And, of course, another windstorm was expected on Tuesday night.

Tuesday was a full day of hauling debris, from all the yards on the block. We recruited help from the neighboring areas, and Carlos would later joke, “what a couple of old guys did on your own, the County needed a crew of 4 and a bulldozer to carry away.”

Caitlin returned with lunch, this time with Father Christopher, a Franciscan monk from the school. In his habit, Chris projected authority — this was not his first rodeo. Chris had been in Baton Rouge for Katrina, and knew exactly how this was going to unfold. There’s always a “respect my authoriteah” phase, where officials at headquarters grasp for quick solutions that don’t involve leaving the office. After denial comes anger, when you blame the victims for getting in the way. So there’s always an initial period of failure in a disaster.

As they unloaded the car, the guardsman insisted that he carry the food for me. “Our mission is to help Americans.” The deputy next to him agreed, “We have been given what we feel is an illegal order. What are they going to do, fire me? They can take this job.”

The D9 driver from LA County stopped by for lunch. “Bring everything to the street, and I’ll take care of it for you.”

Part of every day in Altadena was carrying stuff around. Another part was talking with the guards — National Guard, Sheriff, Highway Patrol — who had been sent there to guard us, to make it difficult. Just talking with those soldiers and officers, sharing our story, and hearing their story, helped them all through the moral challenge they faced: why are they here, who do they serve, and who do they really want to be?

Triumph and tragedy

On Wednesday, all the donations that had been left at the checkpoints had been cleared away. The guards were ordered, in no uncertain terms, not even to let bottled water in. One of the guards at Hill Ave was really enthusiastic, and held an assault rifle as she stood in the street to menace anyone who approached. I chatted up the other guard. “Man, this isn’t right. I signed up to help people.”

At Sinaloa, Carlos and I picked up a box of burritos, where the FBI had rotated in to relieve the Sheriffs for guard duty. Feds are actually quite chill. They’re used to silly orders, and they had brought a drone with an infrared camera to map hotspots.

The public relations battle was far from over. I headed out to walk up to Aaron’s and discuss what to do next, just as young woman strode through the checkpoint. It would turn out to be Laura Kalam, a reporter from Estonia.

From Ny Sou and Avi’s house, you can see the diagonal lines where the wind blew the embers. Some houses burned, while others, right next door, were skipped. You could also see how this was not the sort of cleanup job that one was just going to do with a shovel and a dumpster.

Aaron was giving an interview that would eventually be repeated internationally. It told a story of how residents were fighting to hold on, as an overwhelmed government struggled to comprehend the scope of the damage. Judd was concerned about all the bad air he’d been breathing while chasing stories this week. He appealed to my scientific expertise, so I said, “Cancer risk is about intensity and duration. This is a lot of insult to your lungs, but it’s not like you smoke, right? Right? Well then, you’re done with smoking. You’ve had your lifetime dose.” Laura exchanged notes with the other reporters, and then we headed west toward Lake Ave, where I had yet to go.

It was awful. The English language doesn’t have the words to describe this nightmarish wasteland, which is probably a good thing. My neighborhood was partially burned, but here was only partially unburned. The mutual aid firefighters were still going from site to site, mopping up hotspots, while generators hummed on. At Lake Ave, you could see in what’s left of St. Mark’s school how the embers signed the north and east borders of the grass, but left the rest of it pretty much alone. In this area, where the fire was fed by the dragon’s breath coming out of the canyons, low rock or concrete walls made a huge difference in diverting the heat sources.

Western Altadena, with higher density of houses, was different. There, palm trees showered sparks onto roofs, and that was pretty much the end of that.

Some LA County firefighters stopped when we waved, and Laura asked them some questions. They had just arrived here, so I filled them in on the history. One of the admonished me that I should leave, because it wasn’t safe to breathe the air here. I cheekily replied, “Of course it’s not safe. This is a calculated risk. You guys should really be wearing masks. I have extra — do you need one?”

Laura continued along Altadena Drive into the worst area of the fire, and later sent me a picture of a friend’s house — the only one still standing. When they installed a new roof a few months ago, they had put in an attic fan with a battery backup. Leaving those running, plus a stucco siding and a cinder block wall, had apparently been enough to prevent flames from taking hold.

At the intersection, I met with the detective in charge of the intersection, to explain what I was doing there, and tell him about what we were all doing. Then I listened to him lecture the next truck in the convoy heading up Lake Ave about how there was difference between the Law, which it was their duty to uphold, the Constitution, and Policy, of which starving citizens out of their homes did not sit right with him.

Walking back through the ruins, I took note of a few burbling pipes, and passed the locations onto a neighbor who was still there. He grabbed a nearby water main shutoff tool. “I’m on it.”

I ran into Derek again on Mendocino, and he gave me a ride home. Not that walking would ordinarily be an ordeal, but my lungs were really feeling the smoke, and my lips were blistering. It was time to leave.

At Base Camp, outside Carlos’s again, Derek said, “We need heroes. We need someone to celebrate. We need someone to pin this on, to say they stepped up and did what was needed.” Of course, it was a few hundred people, doing the jobs in front of them. The culture of Altadena — hardworking people who give first — was what had always made this place special. Still, we need a figurehead. Here’s Carlos sharing that message on the TV news.

I asked, “How do we get something where people can come in, get some stuff, clean up, and then leave, because they know they can come back again later?” Eric, a neighbor who I had never met before, and who was there to pick up oranges on his way to visit Fernando, said, “we need a soft opening.” I told Derek, “I need you to ask the public affairs officers if they'll consider a ‘soft opening,’ because that's a phrase that they'll understand and they'll accept.”

That evening, it was time for me to leave. Sleeping in our ash-filled house had taken its toll on me. I brought my loads of belongings we were going to take to the checkpoint at Hill, as a squad of motorcycle cops cleared the path for a bus full of politicians coming down the road. Martha and Oliver met me there with the minivan, and the guardsman insisted on carrying the tubs for me. I thanked him, and he accepted some unsolicited advice from an old man, “You’ll have many choices to make in your service. The easy way is never the right way.” Then I returned the cart to its place by the pink shelf, walked over the yellow line, and left.

Abigail was overjoyed to have me back, and greeted me with her new sidekicks.

The next day, Congresswoman Judy Chu announced a soft opening for Altadena. Aaron called me, exultant: “We did it! We saved Altadena!”

Something neat I found on the Internet

Crush The Memory fits in your pocket. You push the button, and it records what you say, with a good microphone. When you get home, it uploads the audio, and an AI transcribes it. It can store something like 12 hours of audio, which was handy, because there was no wifi in Altadena. I used this to record notes and observations while I was walking around. If you get one, tell Erik Kaiser about it.

Tales from the soccer league

The following Saturday, I was at the field to coach Colin’s soccer team in the first game of the All-Star season. Is it wrong to be amused when the other team coaches complained about how they missed the first weekend of the season, and didn’t get to practice because of the smoke? Or at least admire their chagrin when I tell them, between coughs, that 40% of our team, and both coaches, are homeless? The team motto is, “Who wants it more?”

Two local politicians stand out for swooping into action. AYSO referee and freshman Congressman, George Whitesides, started driving to Reagan National Airport as soon as he heard about the fire. He was here on the ground, listening, pushing, and persuading. AYSO coach and State Assemblymember John Harabedian introduced legislation to fix perverse incentives that would hold up insurance payouts.

Dave Bailey, who coached our daughters’ kindergarten team together, raised money and bought new soccer equipment for everyone who needed it. Why is the managing director of a law firm driving around on a weekday, delivering backpacks to kids? To demonstrate that kids are important, and striving to do good is important.

The uniform supplier, Zeeni, started making replacement jerseys. Dave’s Trophies and Sport Pins International offered to replace awards that were lost from the previous season.

Executive function must correlate strongly with volunteering with kids’ sports.

Colin’s team, The Phoenixes, had a great season, finishing second place in the West San Gabriel Valley. On March 1-2, they’re on to the SoCal championships.

Lessons learned

I have no regrets. Many people have called me since this was first published, to share their regret at not having done more to help. Just as Glenn rotated out when I came in, and Austin started tarping roofs after I left, there will opportunity in the coming years to help.

An electric car is not the same as a gas car when you live a few miles from a national forest.

In retrospect, we had more time than we thought we did. We should have spent another 15 minutes and taken a full suitcase of clothes, and more possessions. Yes, you can buy a toothbrush anywhere, but it’s a hassle.

If you live in California, collaborate with your neighbors for every block to have a high-pressure pump and fire hose. Test it now and again and rotate the fuel on a schedule. Rooftop sprinklers, attic fans, underground water storage, and a battery backup are a good idea, too. Urban areas are just as vulnerable to the avalanche effect, and no amount of funding would have there be enough firefighters.

Politicians were bussed in for photo ops. Every citizen interaction was staged. If you use the chain of command for information, you’re dogmeat.

Derek from Fox News says that the time he spent in Altana changed him forever. He had been a paparazzi, enthusiastic about chasing the shot and getting the scoop. After the narrative battle for Altadena, he's a freedom fighter.

Shameless plug

I am the consulting spacecraft program architect. You can hire me at reasonable rates to help you change the world, from space. And at exorbitant rates, you can hire me to develop the culture, branding, and messaging to win a game your adversaries don’t even know they’re playing. People seem to appreciate it more when they pay more.

Oh, and on the fish subject: twice a year, Martha and I organize a bulk shipment to LA of sustainably harvested seafood that Sierra and Ian catch and source from the Pacific Northwest. Drop me a line if you’d like in on the buying club for October. I literally ran back into a wildfire to save a freezer full of this.

If you liked this and want to catch up, check out previous episodes:

Chapter 0: Recap

Chapter 1: Rethink Everything

Chapter 2: Power Laws and Disruption

Chapter 3: Incentives

Chapter 4: Failure

Chapter 5: Strategy

Chapter 6: Complexity

Subscribe to get more like this. More about me at shantirao.com.

If you’ve made it this far, here’s my request of you: change the world. Do something meaningful to help people, because you can.

Epilogue

It will be several months before we can return to our house, because the cleaning crews are backed up, because the insurance payout process is backed up, and because the Army Corp may or may not turn the golf course into a facility for processing toxic waste. But that’s a whole ’nother story. We are safe for now, in a cottage in Glendale, and I can commute in to Altadena to meet contractors and plan the cleanup. We are looking for a larger house or apartment near school where we can be until it’s safe to go home, whenever that is.

On the Twenty Minute VC, Ben Horowitz recommended reading The Black Jacobins, by C.L.R. James. This is the story of Toussaint L'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution, the only successful slave revolt in history. Horowitz noted how L’Overture led primarily by the lever of culture — through shared values and goals, while building networks to coordinate and share information. I also noted that L’Overture seems to have been the only human on the planet who Napoleon feared. Napoleon sent a historian to observe the revolt, and then repeated L’Overture’s tactics in his own campaigns. Buy it on Amazon, and I’ll get a few cents.

Wow, thank you for sharing the story of what you did, what you all did, what it was like. This was a life changing event and you got to find out that you are one who goes into the breach.

Shanti, thank you for your detailed account. There were many residents who are heros who worked bravely and valiantly to save a community following the worst fire disaster in US History. Having lost my home, I was unwilling to allow the same horror to befall another family. With great focus and determination we provided the necessary support and protection to our community when others were either unable or unwilling to help. It gives Altadena Strong a much deeper meaning. We fought through the smouldering ashes of our devastated town with no water, gas or electricity to provide drinking water, safety equipment, buckets and hand pumps to fight spot fires, five gallons jugs of water to flush toilets, fuel for the generators that ran pool pumps, and warm meals to those who stayed behind to continue to fight to save their neighborhood from the continuing spot fires. Many people had no idea that fires continued to flare up even three weeks after January 7. We learned the tree roots continue to burn for weeks underground. As we rebuild and our neighbors return, never forget the sacrifices made to save the remains of this very special community. We will be stronger than ever when the dust finally clears, but there is still a lot of fighting still to be done to protect our community as it rebuilds. And my heartfelt thank you to all of those brave and resilient souls for what you did in the most trying of times