Free will is a myth

The holdup problem (explained) is where two parties could, and probably should cooperate, but they don’t, because the incentives are wrong. That, and the power of cold emails.

Agenda

Incentives distort judgment

Unsolicited advice

The next big thing

Something cool I found on the internet

Soccer league update

Shameless plug

A small slice of a growing pie

Nowadays, the playbook for raising money for a startup company is pretty standard. It starts with a “seed round,” based on the Simple Agreement for Future Equity (SAFE), and with standard legal documents from Y Combinator, you don’t even need a lawyer. It’s sort of like debt, in the sense that investors get paid back before founders if the business is bankrupt, but everyone act like it’s equity for the purpose of the Section 1202 deduction. It’s also common to bring on advisors, following the Founder Institute’s Founder / Advisor Standard Template (FAST).

You use the seed financing over a few years to find “product-market fit,” whatever that means, which leads to a Series A investment to hire people to increase production and sell the product to actual customers. Series A transactions are mostly cookie-cutters, thanks to standard contract terms from the National Venture Capital Association, which is a good thing because usually you get a “read and sign these final documents today and don’t hold up this deal for everyone else.”

If the Series A succeeds, you raise a Series B, C, or D, to expand production, increase sales & marketing, and add related product lines. When substantial additional investment won’t lead to outsize revenue growth, you sell the company to a private equity fund or retail investors.

What I’ve learned from investing in startup companies is there are soooo many ways this can go wrong, especially in a recession. (There will always be another recession.) How many ways? Let’s count some:

1. The option pool shuffle

The attractions of working for a startup company include long hours, stress, low pay, and stock options. The first three come naturally, but the last depends on the company issuing more shares, which dilutes everyone else. Everyone? Of course not. VC firms are smarter than that. Every new funding round needs new shares to be issued, and those shares come out of how much you thought the company was worth before you took the new money. Smart seed-stage investment funds now ask founders to set aside 20-30% of the company at the start for the equity incentive plan. Venture Hacks dives into it in detail.

2. Inverted yield curve

The nice thing about a SAFE is you can raise multiple rounds with the same terms. Sometimes they’re called pre-seed, angel, or seed rounds. Whatever you call it, you’re unlikely to get your money back. This is where many individual investors and new fund managers participate, because the minimum investment is under $100k.

At seed stage, nobody needs participation rights, because the company will always take your money for the next round. The question is, should you invest upfront, so the company has enough runway to accomplish its plans, or should you hold back, so you can get a better risk-adjusted return later? Let’s look at an example:

ZCo raises $1M on a SAFE with a 20% discount against a $6M cap. After 2 years, the technology looks good, so they raise another $500k, again on a SAFE with a 20% discount, now with a higher $8M cap.

18 months later, ZCo’s product looks good, so they start to raise a Series A. They raise another $375k on a bridge round, before selling 35% of the company for $10M at a pre-money valuation of $18.6M.

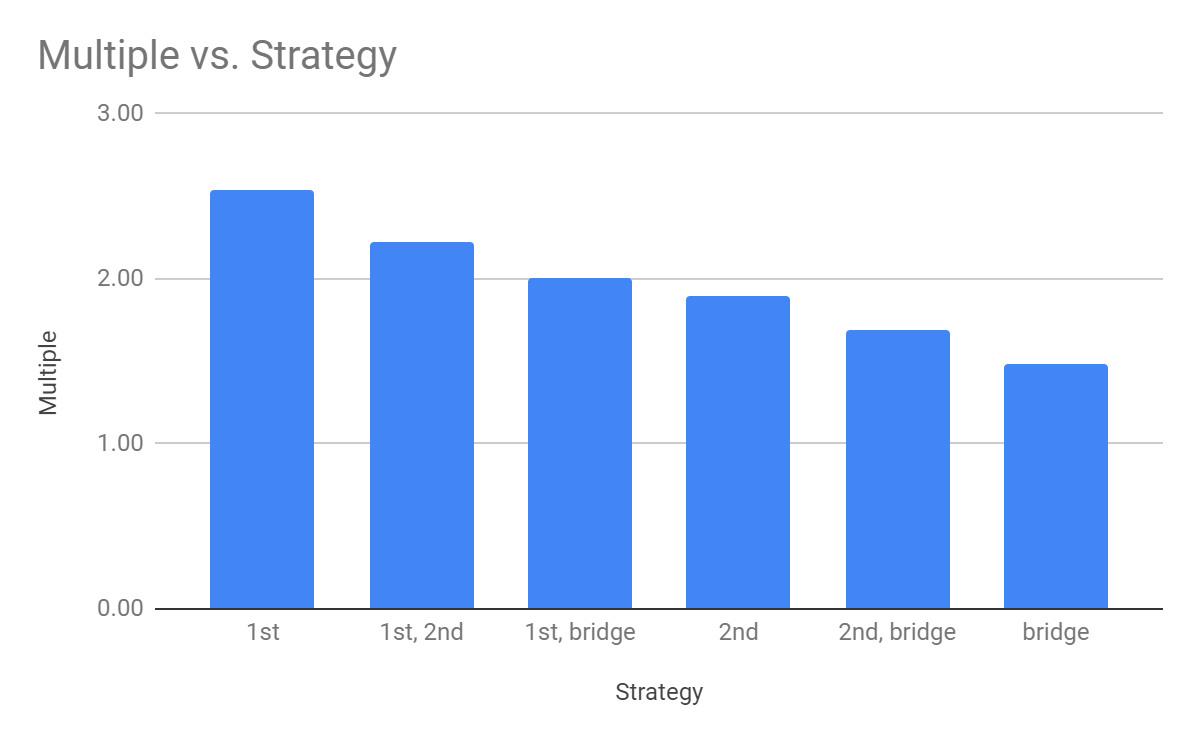

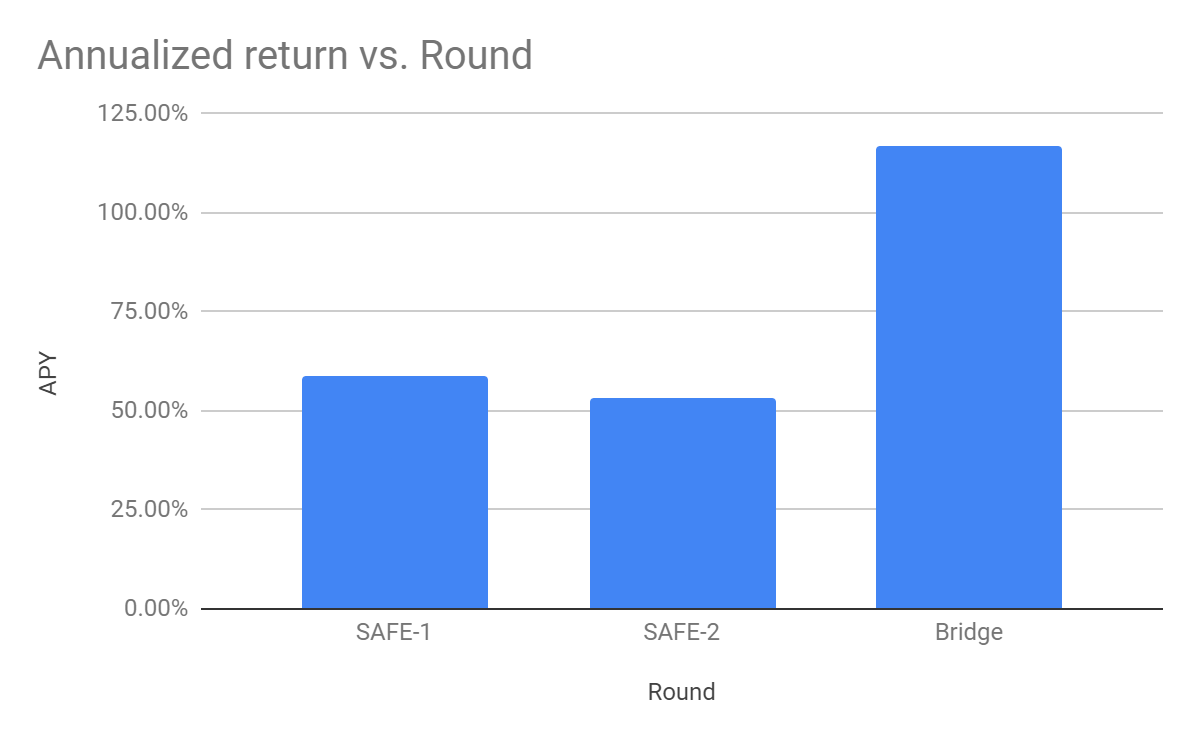

You can play along in my model cap table. From 6M to 18.5M should be good for those early investors who had a $6M cap, right? In fact, their equity would have appreciated 2.5x after 4 years. The investor who held back half her money for the second SAFE got 2x. Not bad.

The people who waited longer, until the bridge round, have a much lower multiple — but they only had to wait 6 months. If you look at the annualized return, it makes much more sense to hold your cash back as long as possible, especially if you expect that the risk of failure decreases over time.

That’s the inverted yield curve: the longer you wait to invest, the better your returns are. In fact, the best strategy is not to invest in early startups at all, but wait until all the risk has been retired and the early investors have run out of money — then you can swoop in and double your money in only a few months.

It’s not unheard of for investors to urge founders to delay raising a Series A, so they can fund a bridge round that makes the fund’s balance sheet look good.

How do you avoid this trap?

Plan ahead

Choose milestones and terms that ensure consistent yields

Have off-ramps to grow organically

Thanks to Alan Cornford for showing me how to calculate the PPS!

3. Stick it to the other guy

Downrounds are not necessarily a bad thing, which is why I always ask for a MFN clause as an investor. A MFN clause means that if any later investor is offered a better deal, or lower share price, or whatever, you have the option to switch your terms to those terms. MFN clauses are good for founders, too:

It makes it less risky for the first investors to say, “yes,” without worrying that we’re in a recession.

The first investors can accept a valuation that they know ridiculous. At least it gets them started. Eventually, they’ll take money from an institutional investor and the MFN SAFE price will automatically compensate the angel investors.

It prevents future investors for asking for side-deals. “I’d love to accept your Total Bastard Termsheet, but we have a MFN clause, so all the other investors would get the same preferential treatment, which means nobody would get preferential treatment. How about we just do an ordinary deal instead?”

It let you ratchet up the valuation steadily, thus ensuring that the earlier investors are rewarded with a risk-adjusted yield. This encourages people to invest early, rather than holding back capital for when you’re desperate to close a bridge.

4. Liquidation preference

Series A investors are pretty smart, and one of the tools they use to avoid losing money is liquidation preference: when the the company is sold, or exited, they get all their money back first. Whatever is left after that, is divided among the shareholders.

In the above example, the bridge round share price was $1.37, and the Series A price was $2.06, for a company valuation of $28.6M. If you subtract $10M from that (the liquidation preference), and divide by the total number of shares, you’re left with $1.34/share. That’s right, the founders’ and SAFE investors’ equity value actually goes down by 35% after receiving venture capital, while the venture fund’s stake goes up 65% instantly. Mind you, 20% of that gain is the fund manager’s fees.

That 2.5x multiple eroded down to 1.7x, because of the liquidation preference.

Now, valuations are really just a way for the various investors to divide up the long-term gains, and the only way anyone gets paid is for there to be a big exit much later.

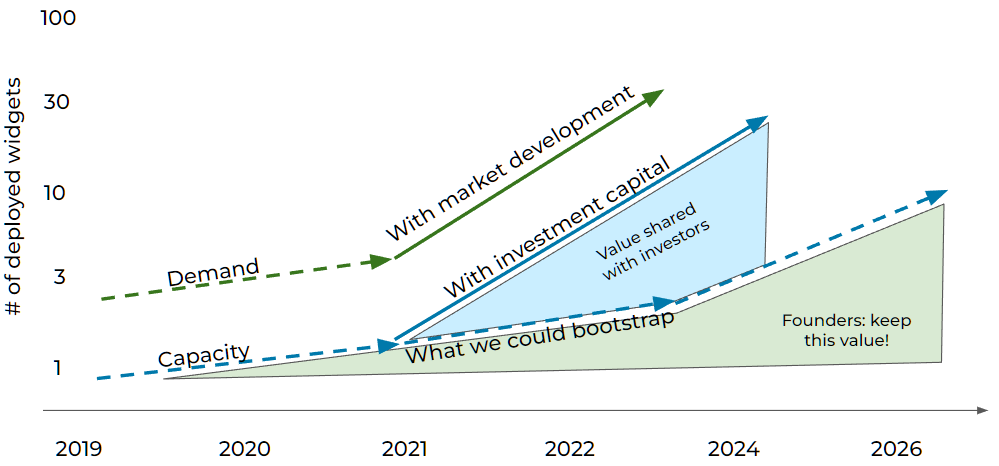

How do you deal with this? First, start with lower valuations early on, to leave room for more growth. The SAFE investors underwrite technical risk reduction, so that the Series A can be about scaling. This chart, from my Big Data From Space Playbook, illustrates how venture investment should go toward demand (sales & marketing) and capacity (production).

If the company has paying customers and could grow organically, or with bank loans to fund production expansion, then the green area is what the founders have created for themselves and their seed investors. Then, show how investment will increase demand or capacity. That increases the area under the sales curve, and the growth relative to what you could do without new investment is what the new investors deserve to share. It works best when the value has to be plotted on a log scale.

Angel investing

Everyone seems to have a startup seed fund nowadays. Should you invest in startups?

No. Most sensible people say you should put no more than 5-10% of your savings in high-risk investments. They also say that if you make only one investment, you’re likely to lose it. A typical venture capital fund will make 10 investments, and maybe 1 of those will return more than twice the value of the fund. The rest are likely to be write-offs. But that’s ok, because the rare winner more than makes up for it.

So if you’re investing as an individual, and you have 5% of the accredited investor minimum of $1M to work with, you can make two $25k investments. There’s an 80% chance that neither of those will be winners. It makes more sense to pool your resources through groups like Tech Coast Angels, or invest in seed funds. It costs more, but you get more at-bats. Mind you, they say the smartest angel investors in Silicon Valley are simply investing $10k in anyone who is breathing — due diligence costs more than missing out on the next Uber.

“Why don’t you get some billionaire to pay for X?” is a question I am asked, surprisingly often. Let’s say you actually have that much money. Then if you followed prudent financial advice (how else did you get to have that much in the first place?) would want to distribute at most 5%, or $50M, across 10, or better yet, 100 different ventures. The problem is not that there are too many billionaires, it’s that there aren’t nearly enough

The Next Big Thing

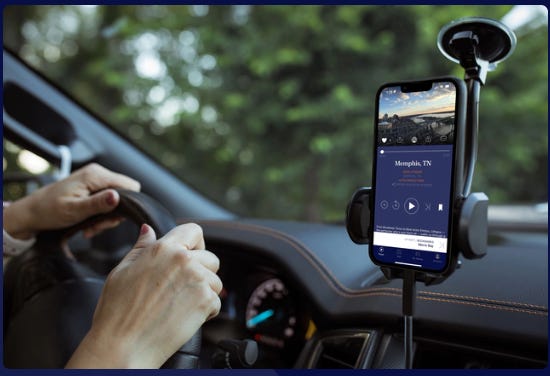

Summer vacation season is here! Get the Autio app for iPhone.

What are you trying to do? We want people to feel like they belong in America, as part of an interesting civilization that has a past and a future. We make road trips more fun by telling stories about the places you visit as you drive around.

How is it done today, and what are the limits of current practice? You could do research online about everywhere you’re traveling to, or you could hire a local guide. But then you’d have to take your hands off the steering wheel.

What's new in your approach and why do you think it will be successful? Autio, formerly HearHere, tells you stories about the places you are visiting as you drive around the country. Autio’s storytellers have researched, edited, and recorded thousands of stories about human and natural history. When you drive near where something happened, the iPhone app pauses your playlist and tells you the story.

What difference will it make? The drive from Vegas to St George is 150% more interesting* now that I know a little more what those who preceded me did.

* arbitrary units

What are the risks and the payoffs? It took a while to create the initial library of audio stories. Now, a shocking number of people use Autio for virtual travel, exploring the map from home. Besides the growth in subscription sales. I think the real value of Autio is to bring people closer together by understanding our mutual history on this continent. Telling stories about first peoples, pioneer women, and immigrant workers are central to the founders’ vision.

The app comes with 5 free stories. One of my favorites, for the stretch of I-5 from Olympia to Portland, is The Pacific Northwest From The Beginning, narrated by Kevin Costner (also an investor, along with me, the AAA of Washington, and GoodSam). Woody, the founder of Autio, found me through a cold email, and we kept in touch for a year before I invested. He also got 10 pages of bug reports and feature suggestions.

The research team also comes up with stories that don’t have a place, so they go on the blog. Here’s one to think about over the summer: https://hearhere.com/2020/09/01/beyond-bbqs-parades-the-long-struggle-for-labor-day/

Something cool I found on the internet

High school language classes should teach how to write advertising copy. Failing that, check out the MailShake Cold Email Master class.

I found it through Hustle Fund’s blog (which I read religiously). Their new Uncapped Notes videos have targeted advice for startup founders.

Soccer club

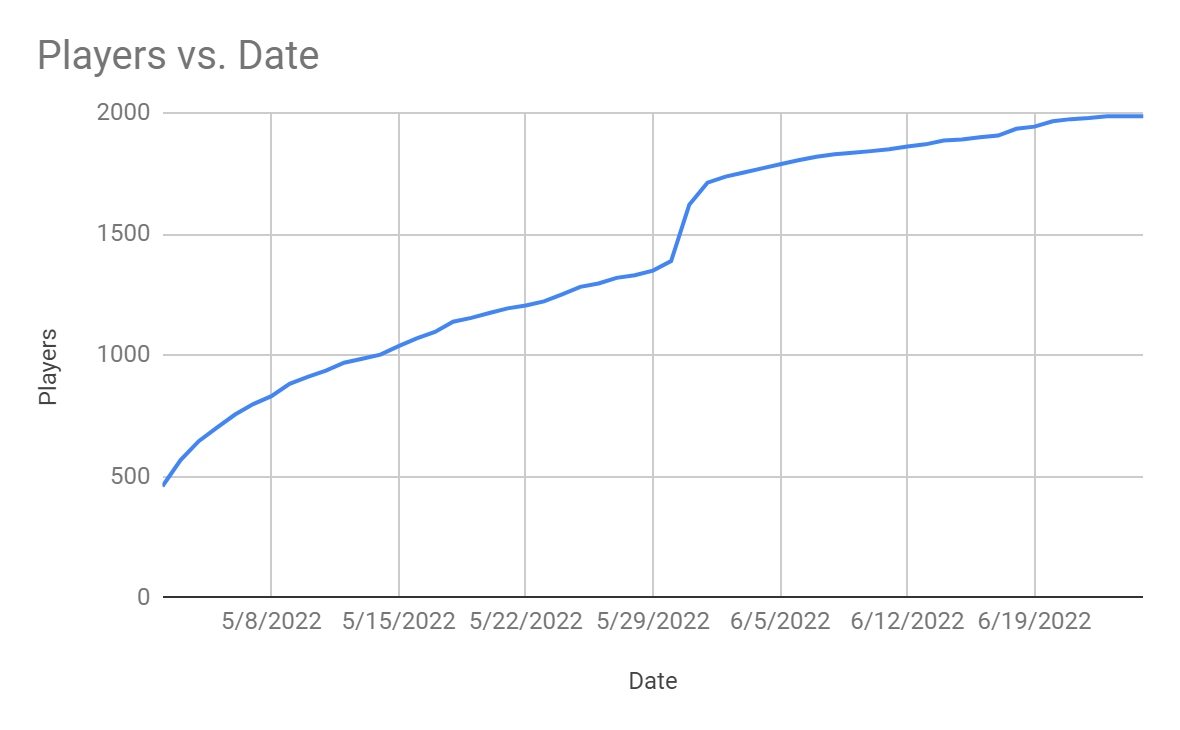

We’re well into registering kids to play in AYSO Region 13, the soccer league I help run. What does the data tell us?

Facebook ads seem to have negligible impact.

We used to wonder if the club were saturating the market. If that were the case, you’d expect the rate at which kids register would decrease over time, as the supply were depleted. Instead, we see a steady increase over time. If you draw a straight line through the registration curve, it crosses the 3000 mark on Labor Day, which would be up from 2400 last year and 2100 before the pandemic.

Advertising has marginal utility. Sending an email reminder at the end of May did motivate many immediate registrations, but those people would probably have gotten around to it in the next few weeks anyway. At the end of June, the same number of kids/day sign up as did in the middle of May.

This suggests that there may be underlying causes for why not all parents might not plan their kids’ activities 6 months ahead of time. Maybe they’re thinking about finally leaving California. Maybe their kids aren’t ready to commit that far in the future. Maybe they’re too exhausted to worry about anything new until after school starts. Whatever it is, I think institutions that serve families should invest in being flexible, because risks in a transaction should be managed by the party with the most data, and that’s not the parents.

Shameless plug

Do me a favor and forward this to someone you like!

Speaking of cold emails, the CTO of MinWave found me. She has a really neat invention — metamaterials for doing analog computations inside a waveguide, such as filtering and spatial compression, leading to better, smaller, and cheaper RF waveguides devices. This could potentially boost signal gain, and also reduce RF transmit power, in 5G towers by 20%, while also saving money. I quickly put them in touch with my clients to start discussing collaborations.

It’s easy to access my network — just tell me what you want!

You know how I put “Stealth Startup” on my LinkedIn profile? Well, after throwing away 5 business plans because the cap tables would never work out, I found one that works. That’s right. I really am running a Stealth Startup, it’s a space company, and we’re raising money. A lot of money.

As Gabe Dominocielo of Umbra says, “making a lot of money is a lot of fun.”

If you liked this and want to catch up, check out previous episodes:

Chapter 0: Recap

Chapter 1: Rethink everything

Chapter 2 Power Laws